Pre-1790 Census:

Temporarily apportioned house seats for Kentucky and Vermont, awaiting the 1790 post-census reapportionment (Feb. 29, 1791 legislation)

1820 Census:

In December, 1821, Secretary of State John Quincy Adams reported the results of the 1820 census to Congress, but he had some bad news: some of the results from Alabama (which had only just become a state in 1819) were very, very late---so late that a few counties’ worth of data had to be omitted from the official state population. Congress initially passed an apportionment law (March 7, 1822) that increased the size of the House from 187 seats to 212 seats, with Alabama’s delegation growing to 2 seats. Then Congress reconsidered in 1823, bearing in mind the missing figures from Alabama, and decided to increase the House by one more seat, to 213, and to give that added seat to the uncertainty-plagued state of Alabama.

1850 Census:

After the 1850 census, the first returns made it back to census headquarters in August, 1850. But the returns from California took until February 1852 to arrive, and when they got to D.C., they were incomplete: a fire in California had burned some substantial number of the census records and the census had no records for San Francisco, Santa Clara, and Contra Costa Counties. Congress only had a rough estimate of California’s population to go on. The 1850 census mostly represented a break [link to break section] from the Count and Increase tradition---the size of the House had been set ahead of time at 233 seats (so as to neither increase nor decrease the size) and was supposed to be apportioned automatically. But in response to the California data disasters, Congress interfered in its planned automatic system and added one extra seat for California (so that it had 2), increasing the House to 234 seats (June 30, 1852 legislation).

1870 Census

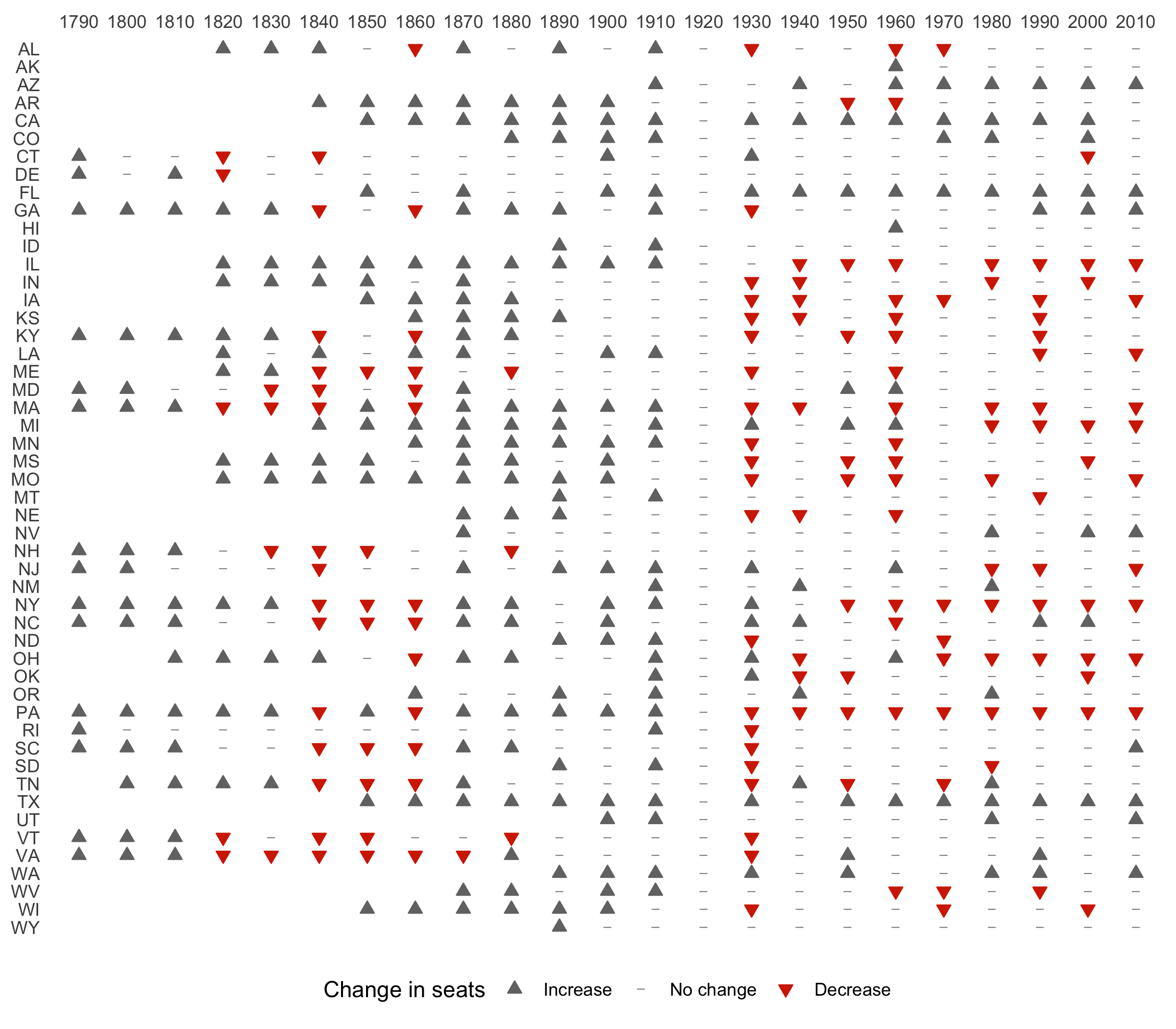

The 1870 census count took place in the shadow of the Civil War. Its returns drew immediate criticism from all over. It was, in the description of historian Margo Anderson, “plagued with undercounts, local demands for recounts, and poor responses to questions.” Congress initially passed an apportionment that increased the size of the House by 40 members to 283 seats---at that size, only New Hampshire and Vermont would lose a seat. (Virginia appears to have lost a seat in our visualization, but that is another anomaly caused by the creation of West Virginia.) This increase would have been entirely ordinary within the Count and Increase tradition. But Congress reconsidered in May 1872, adding another 9 seats, which was necessary to ensure that no states lost a seat, and possibly also necessary to get enough votes to pass the bill. (Because of the Constitutional requirement for proportionality, saving a seat for a small state like NH or VT could sometimes mean handing out extra seats to many other states too.) A very large increase in the size of the House helped make do after a very controversial census.

1950 Census:

By 1950, the Count and Increase tradition had ended. The House was effectively capped at 435 seats. That is why the temporary increase of the House to 437 seats on the eve of the 1960 census looks like an anomaly. Hawaii and Alaska were admitted to the union and each was given one temporary seat until the next census. After the 1960 count, the reapportionment was conducted again to distribute the number of house seats back to 435.